Applied Germicidal Ultraviolet Technology

by Jeff Stines, American Ultraviolet

Over the past year I have had the opportunity to engage with people from more diverse backgrounds (in every sense of the word) than I have in the more than 20 prior years I spent building, designing, marketing, and selling applied ultraviolet technology. I have met some brilliant and enthusiastic people along the way, which is definitely a silver lining of the global pandemic that has forced all of us to reevaluate what we thought we knew as of February 2020.

Over the past year I have had the opportunity to engage with people from more diverse backgrounds (in every sense of the word) than I have in the more than 20 prior years I spent building, designing, marketing, and selling applied ultraviolet technology. I have met some brilliant and enthusiastic people along the way, which is definitely a silver lining of the global pandemic that has forced all of us to reevaluate what we thought we knew as of February 2020.

I have found that my extensive experience with ultraviolet equipment (from manufacturing and assembly, to theory and practical application), is relatively rare, in the context of the typical business professional; and the ability to share what I know with interested and enthusiastic people looking to make our world a safer place has been the most rewarding part of the exponential growth American Ultraviolet, and others in the UV market, have seen over the past year.

When speaking with all the newly interested parties over this time period, I found that providing science-based, factual information - while giving as much attention to the challenges, as to the benefits, of implementing UV technology for microbial reduction - has really opened up helpful and productive discourse regarding the established technology we've been offering since the 1960's, as well as emerging technologies that are receiving a great deal of attention from the media.

Past Meets Present and Looks at the Future

Here's my takeaway from these interactions – though the future looks bright for applied UV technology, we must make sure we're using the right tool for the job. Just because an emerging technology has great promise and potential (or really slick marketing), doesn't make it the right answer for every situation. And just because a version of the emerging technology has been around for more than 60 years doesn't make the original solution obsolete.

The most glaring instance of the latter statement has been the lack of consideration given to Upper Air UVGI. Simply put, the hot (98.6° F) air you breathe, cough or sneeze out of your body is roughly 30° warmer than room temperature (typically 68° F). This germ-laden warm air rises above the air in the room and sits up there until it cools off; then it sinks back down to the level of the occupants of the room. So, as an example, if Billy enters the same room anywhere from 30 seconds to 30 minutes after Sally previously coughed in, he has the opportunity to inhale a big, hearty petri dish full of what Sally coughed out. Sharing is not caring in this instance.

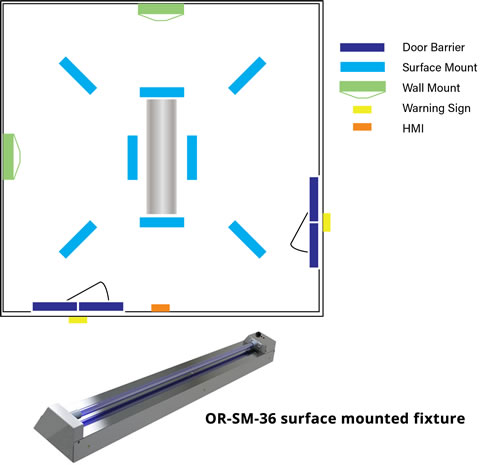

By encouraging good air mixing in shared spaces (restaurants, post offices, waiting rooms, offices, classrooms, gyms, etc.), and incorporating louvered upper air UVC fixtures from American Ultraviolet that direct UVC energy into the air at, and above, 7.5-feet from the floor, we can target the very space  where those nasty microorganisms are hiding, and attack them while they are airborne, which typically requires far less UVC energy than surface applications (like germs protected inside mucus from a sneeze on a chair or table). The UVC Zone in the upper air exists above the area of the room occupied by people, so the fixtures can safely remain turned on 24/7 with people occupying the space.

where those nasty microorganisms are hiding, and attack them while they are airborne, which typically requires far less UVC energy than surface applications (like germs protected inside mucus from a sneeze on a chair or table). The UVC Zone in the upper air exists above the area of the room occupied by people, so the fixtures can safely remain turned on 24/7 with people occupying the space.

This is not a new concept. These types of upper air UVGI fixtures are what my grandfather started building in a garage in New Jersey in the 1960's to inactivate tuberculosis. This is still an excellent solution to inactivate microorganisms. The fixtures mount to a wall with two screws, and plug in to a standard outlet, so you don't even need an electrician to install them.

If it's that simple, you might ask, why isn't Upper Air UVGI a requirement in schools, gyms, restaurants, etc.? There are several answers to this question, including:

Properly designed and assembled UVC fixtures can cost, at the upper end of the spectrum, more than $1,000, which might seem expensive when there's not a global pandemic costing your facility at least that much every single day.

Though proper knowledge about room area coverage per fixture is published, and available, it is not very widely known, possibly because a good deal of the information dates back to the middle of the 20th century and has been lost to many (including some in the UVC industry) for decades.

New technology, such as the "safe for humans" (a statement I take with a huge grain of salt) "Far-UVC" 222nm Excimer lamp modules, could potentially offer the benefit of being able to provide germicidal energy to both upper air, and surfaces in spaces. However, the duration of time and intensity of 222nm energy that is considered "safe" for human exposure is not, to date at least, scientifically documented to my satisfaction. Nonetheless, this technology is being marketed as the ultimate answer for communicable pathogen mitigation. Drawbacks of this emerging technology that are consistently overlooked include the cost, and the useful lifetime of the equipment. Current useful lifetime of the top performing modules is about 3,000 hours, which is only 1/3 to 1/6 of a well-made low pressure mercury vapor UVC lamp (the "old" technology). This means changing out your new, "high tech" solution consumables quarterly. The cost is also 3-5 times that of standard UVC lamps.

So, doing some quick math - if your UVC system requires a single, 17,000-hour lamp that costs $100, your annual operating cost is about $50. In contrast, the 3,000-hour lamp costs $300, and needs to be replaced every 3 months, so the annual operating cost is about $1,200. By the time you spend $100 on a standard UVC replacement lamp, you would have spent $2,400 (or more) on your "advanced solution."

So, doing some quick math - if your UVC system requires a single, 17,000-hour lamp that costs $100, your annual operating cost is about $50. In contrast, the 3,000-hour lamp costs $300, and needs to be replaced every 3 months, so the annual operating cost is about $1,200. By the time you spend $100 on a standard UVC replacement lamp, you would have spent $2,400 (or more) on your "advanced solution."

UVC LEDs suffer a similar downside, because of significantly lower UVC output per linear inch of light source. So they don't last as long (typically only 1,000 hours), they cost more, and they're less effective in any application larger than a toaster oven-sized exposure chamber.

All this is not to say these technologies won't eventually become outstanding solutions, just that they are not out of their infancies yet. The 222nm technology needs some refinement in cost and longevity, and the UVC LED offerings need to stick to small area applications requiring intermittent use until the lifetime and UVC output make UVC LED a more effective solution.

Visit the Disinfection Update E-newsletter archives (which begin with March 2020) to read helpful stories about the effectiveness of UVC Disinfection.

None of the American Ultraviolet UVC products detailed above are certified, or approved under any applicable laws, as a medical device, and as such, American Ultraviolet, and its Representatives and Distributors, do not currently intend for them to be used as medical devices anywhere globally. Products have not been evaluated by the FDA.